The context

On the 6th and the 7th of October 2018, Romania organized a referendum in an attempt to redefine the concept of family in the Constitution. Even though the civil law explicitly forbids same sex marriage, the conservative organization Coalition for the Family (Coaliția pentru familie) started in 2015 to gather the number of signatures the law requires (3 million) in order to organize a public consultation on this specific issue[1]: reformulating the constitutional article regarding the family, so as to replace the gender ambiguous term “spouses” with their traditional correspondents – “husband and wife”. The initiative was approved by the Constitutional Court in 2016 and by the Chamber of Deputies in 2017 and received the final approval from the Senate on September the 11th, 2018, with 107 votes for, 13 against and 7 abstentions, validating the proposal for the constitutional revision.

Not only would this definition have been discriminatory towards the LGBTQ community, but it would have also left out many other forms of communion which, in the opinion of the Coalition for the Family, do not reflect the realities of the “traditional family”, such as single-parent families or the situations in which children are raised by their grandparents (a common reality throughout Romania, as more and more adults go abroad, seeking better salaries and better working conditions).

The idea of a constitutional revision for this purpose has fractured the Romanian society, which has been divided between the supporters of this initiative and its opponents. The opposition was mirrored in the media, in the political debates, and on the streets of the big cities of Romania where manifestations and marches have been organized since 2016 to oppose or to support this initiative. Even the international community reacted differently to what was about to be the first Romanian civic initiative after the fall of communism in 1989. While organizations such as Amnesty International, the European Commission on Sexual Orientation and Law and even 33 members of the European Parliament declared their opposition to this constitutional revision and even petitioned Romanian senators to vote against it, other MPs welcomed the idea and asked for the organization of the referendum.

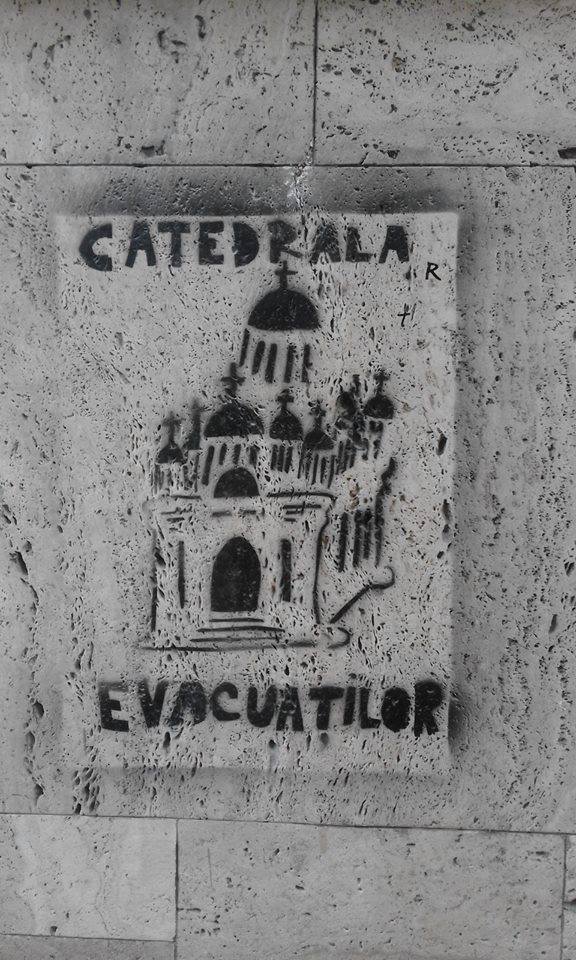

Despite the fact that the referendum failed on low vote turnout[2], the political parties supporting the initiative, as well as the Coalition for the Family, didn’t spare any effort or resource in order to persuade the voters to cast their ballot. Nicknamed “the referendum of hate” by those opposed to the idea, this initiative was backed up by the most aggressive propaganda Romania has witnessed in the recent years. Officially supported by traditional political parties, as well as by the Romanian Orthodox Church, the responsibility was nevertheless claimed by the Coalition for the Family, which essentially meant that the campaign for the referendum couldn’t follow the same pattern as the electoral campaigns, from financing to the promotional materials. Even though huge banners inviting citizens to vote “yes” invaded the big cities, raising concerns about the way authorizations were obtained and about the sponsorship behind this costly materials, the main way to catch people’s eye was through a strange and poorly understood “street art campaign”.

But what forms of street art were used? What were the messages transmitted through this “street art campaign”? How was this rhetoric of hate mirrored by it? How far did their arguments pro and against constitutional revision went?

Forms of street art

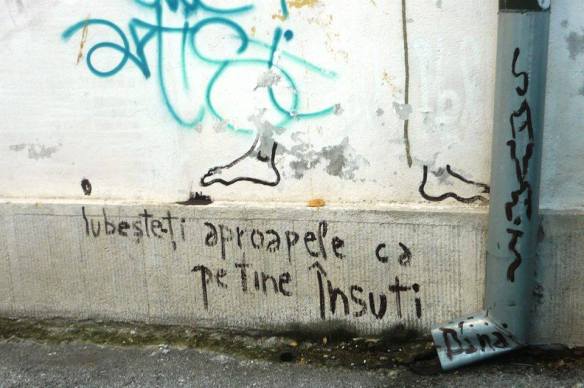

It is commonly acknowledged that “street art refers to stencils, stickers, and noncommercial images/posters that are affixed to surfaces and objects (e.g., mail boxes, garbage cans, street signs) where the owner of the property has NOT given permission to the author. Thus, at a bare minimum, in most countries because of its illegal nature, graffiti and street art are legally speaking considered acts of vandalism”[3]. Thus, given the ambiguity of the involvement of public authorities, the most convenient way of conquering the public space was through stickers, posters and flyers scattered around the city. If around the country, local orthodox churches and priests took over the propaganda, Bucharest is a more complex case study, given the sociological traits of the residing population. Younger, more educated, less prone to manipulation and more dynamic than any other one, Bucharest’s electorate had to be approached accordingly.

As Cedar Lewisohn pointed out, in the recent years, “graffiti and street art have followed the general tendency of the endless flow of information and constant “noise” of the world. Both can be seen as subversive forms of advertising”[4], triggering virtually the same reaction as shiny billboards and colorful banners at a subconscious level. This is how the homophobic and aggressive messages raised from the constant buzzing of the crowded cities. Vividly colored and accompanied by suggestive text and images, the stickers have come to cover street lights, trash bins, shops’ windows and walls, feeding off of the rhetoric of hate towards alterity and proposing a type of toxic unity aimed at the protection of the traditional values that are said to define the Romanian people and its culture.

Illustrated arguments in favor of the referendum

- Unity

This year marks the centennial of modern Romania and the country has been subjected to a “rebranding” process. Slogans proposing unity and popularizing the sense of togetherness are now completing the image of public institutions. Interestingly, in the stickers shown above there is no logo representing the Coalition for the Family, as if we are talking about everybody’s initiative, a commonly accepted one that doesn’t need any further presentation.

- Common-sense

The propaganda for the referendum portrays the initiative with the colors of a true revolution, the revolution of “common sense”.

- Vote as civic duty

Moreover, the participation is encouraged by means of association with the myth of the Revolution of 1989, when people allegedly died for our right to vote. Therefore, casting one’s ballot means honoring the martyrs who sacrificed for us to build a powerful democracy on the grounds of the vanquished dictatorship. (left side)

A sticker, which reads “You said you care? Vote in the referendum!” conveniently placed next to another one that reads “Fuck PSD!” (the political party currently governing Romania), still fresh from the protests against the government which took place in August 2018[5]. (middle)

The right side sticker encourages us to “Write history! Come!”, in an attempt to emphasize the difference that our vote can make.

- Preservation of Romania’s traditions and values versus decadence

According to the Coalition for the Family, a yes to referendum equals the preservation of the family, Orthodox faith and tradition: “For Romania, for the family, for faith, for tradition: vote yes on the 7th of October!” (image on the left).

The right side sticker insolently asks what would you choose between the homosexual or the Romanian identity, as if the two were mutually exclusive. The “decadent” lifestyle of homosexual couples is hereby opposed to the purity of the sacred union between a man and a woman.

- Political and sexual education

A poster showing the proper way to vote in the referendum: just choose “yes” (left image)

“Fasten it correctly! (In Romanian, this wordplay can also mean “have sex with whom you are designed to”) Vote yes!”

Paradoxically, one of the messages of the Coalition for the Family is “Do you feel discriminated against? Go out and vote!” (left side image).

“In other countries, pedophiles are asking for their rights. And you still don’t vote?”

- Demonizing the adversary

If you don’t go to vote you are either a communist or a homosexual, as resulted from these messages.

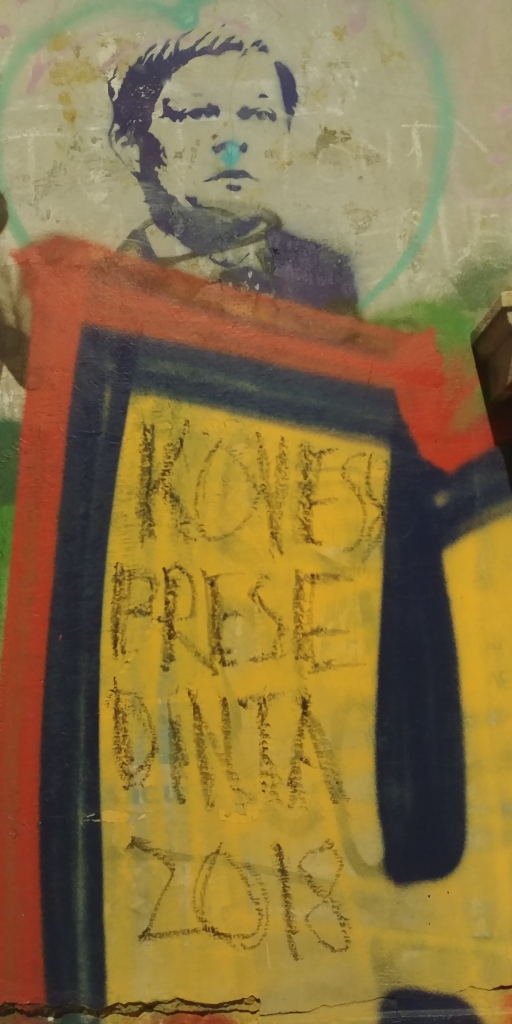

We can find something appealing to any political sensibility as well! Here (left side image) we have a stencil associating the same sex marriage with Marxism or even communism. Following this rhetoric, we must understand that allowing same sex marriage will automatically carry us back to our communist roots.

The right side image represents a sticker suggesting that homosexuals are the only ones who are going to boycott the referendum, urging the people of good faith to go out and vote. In a political landscape devoured by electoral apathy[6], the refusal to participate during a public consultation acquires a whole new meaning- we are now talking about boycott, a conscious collective attitude, a means of participation though withdrawal, through a self-assumed silence.

- Protect Romania’s children

Another very strong argument to which many of Romanians are sensitive to is related to children. Therefore, many banners, posters and stencils were exploiting this theme, encouraging people to go to vote in order to “ Protect Romania’s children! Come to the referendum. Let us be 6 000 000!” or as it appears in the above mentioned stencil, “save the children’s future!”

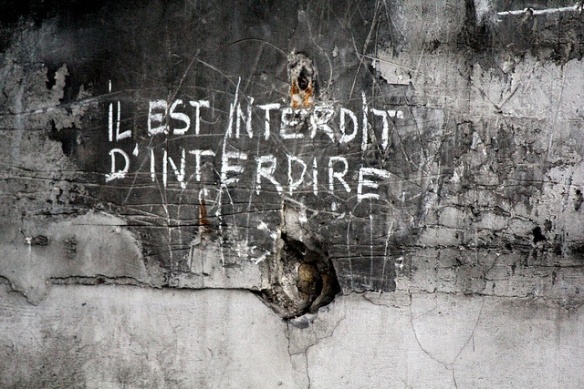

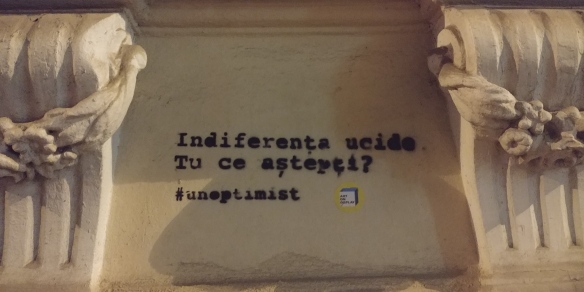

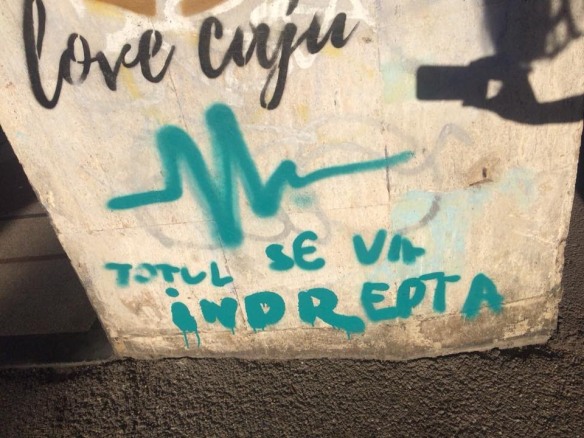

Illustrated arguments against the referendum

The counter campaign for the “referendum on normality” has been equally powerful and visible. Public figures have launched their own campaign: “You cannot vote on love!”[7] and an extremely poignant video based on “The Handmaid’s Tale”[8] has been released in order to raise awareness of the way this kind of camouflaged political interests can change our reality.

“You cannot vote on love! On the 6th-7th October, stay at home!” (right side image)

#boicot (#Boycott) and #stauacasa (#IStayAtHome) where used on social media during the counter-campaign.

“Marriage = two persons who love each other” (right side image)

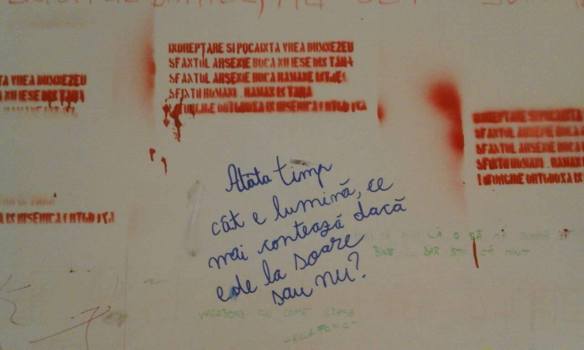

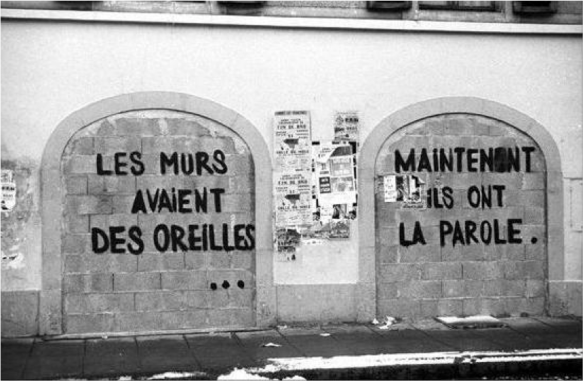

The impossible dialogue

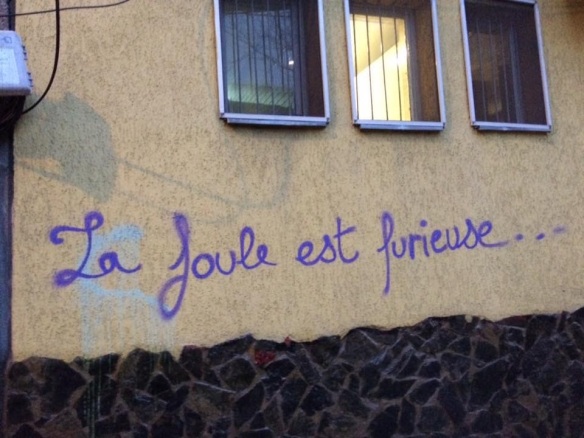

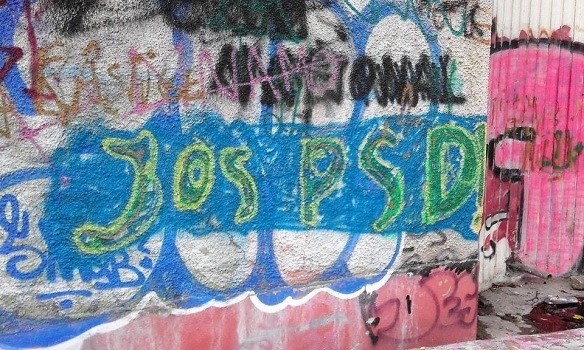

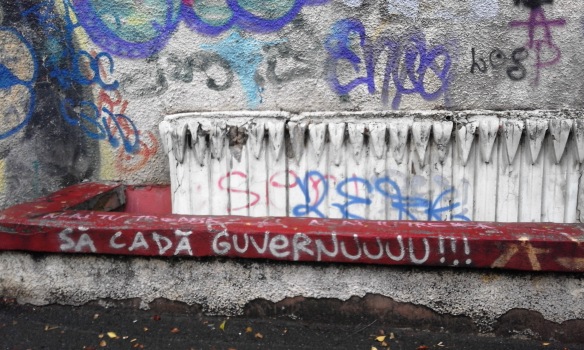

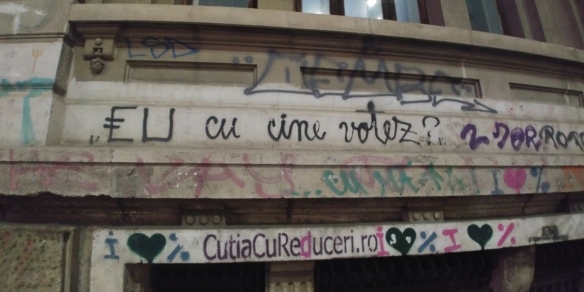

The debate in the mass media, or on social media was obviously an impossible dialogue, which was mirrored also by the street art.

“6th-7th of October go to vote” was countered by those who believed that you cannot vote on love.

An intervention on a pro-referendum banner stating “Hate and Disunion. 10.08.2018. We don’t forget! We don’t forgive!” is recalling another recent anti-government protest on August 10th, 2018, which ended with a violent response from the police against peaceful protesters.

Few days later, the banner was taken down because it contained or reproduced the Romanian flag which, according to the Law 334/2006[9], was forbidden.

The choice of street as a medium for the propaganda in this specific case is by no means coincidental. An issue brought on the government’s agenda by the civil organization Coalition for the Family has slowly imposed itself on the public agenda as well, by invading the whole public space and concentrating all the attention of the targeted electorate. The anonymity of the messages is perhaps the most striking aspect of this ample choreography: even though everybody knows who claims the responsibility for the whole affair, nobody has publicly taken credit for these very creative slogans. The stickers have invaded every inch of public space available in the same way electoral posters cover the designated areas during the campaigns, with one significant difference: the latter miraculously disappear in the aftermath of the elections, while the former are here to stay for as long as we allow them to, filling the streets with the hatred and the shameful violence we’ve shown, as a permanent and painful memento of the way we lacked compassion when it was needed the most.

[1]„Hundreds injured in Romania protests as emigrants return to fight corruption”, The Guardian, 11.08.2018, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/aug/11/hundreds-injured-in-romania-protests-as-emigrants-return-to-fight-corruption

[2] Joe Sommerland, “Why is Romania holding a referendum on same-sex marriage and what might a ‘yes’ vote mean?” The Indepenent, October 7th, 2018 – https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/same-sex-marriage-romania-legal-vote-gay-rights-lgbt-lesbian-civil-partnership-a8568031.html.

[3] Luiza Ilie, „Romanian constitutional ban on same sex marriage fails on low vote turnout”, Reuters, DATA https://www.reuters.com/article/us-romania-referendum/romanian-constitutional-ban-on-same-sex-marriage-fails-on-low-vote-turnout-idUSKCN1MH0XI .

[4] Jeffrey Ian Ross et al (eds.), Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art, Routledge, New York, 2016, p. 1.

[5] Cedar Lewisohn, Streetart – The Graffiti Revolution, LOC Tate Publishing, 2008, p. 92.

[6] As shown by the Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (https://www.idea.int/data-tools/question-countries-view/521/252/ctr); Mihaela Mihai, “The Political Apathy of the Youngest Romanian Voters: Lessons to Be Learnt”,, Paper prepared for the Canadian Political Science Association Annual Conference, York, 1-3 June 2006 (https://www.cpsa-acsp.ca/papers-2006/Mihai.pdf)

[7] Adelina Mărăcine, „Mai multe vedete într-o campanie de boicit a referendumului” in Adevărul, 27.09.2018, https://adevarul.ro/entertainment/celebritati/video-mai-multe-vedete-intr-o-campanie-boicot-referendumului-o-clasa-politica-corupta-nu-dreptul-decida-iubesc-1_5bac94c9df52022f75e68089/index.html

[8]„Children of the Referendum”, a counter campaign: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4C6f_HGn338

[9][1] Law 334/2006, art. 36, http://www.roaep.ro/legislatie/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/LEGE-Nr.-334-2006.pdf , accessed on October 22, 2018.

Irina Bădescu

Oana-Luiza Barbu